1. INTRODUCTION

The rapid development of modern society affects even contemporary art. In step with industrial development, innumerable materials are available, and new materials, in turn, give birth to fine art that involves diverse methods beyond traditional ones by dint of an artistsŌĆÖ experimental challenges and creations. Thus, it is difficult to predict the types of damage to contemporary artwork because of the diversity of materials and experimental techniques used. This results in difficulty in its conservation. Furthermore, the artistŌĆÖs message inherent in a work has its own specialty and uniqueness, making conservation treatment of contemporary works of art even harder.

During interpretation of the authenticity of contemporary artwork, immaterial aspects may play a more important role than material aspects. Thus, conservators attempting to maintain the artistŌĆÖs ŌĆ£intended appearanceŌĆØ should conduct conservation treatment after grasping the artistŌĆÖs exact intention so that the artistŌĆÖs message can be conveyed to the audience correctly(The Getty Conservation Institute, 2016).

Artists play a central role as sources of information in decision-making processes for the conservation of contemporary artworks, and so may suggest directions for successful conservation treatment. Moreover, collaboration with artists could be an important process by which enhance the trustworthiness of the originality of the work. Therefore, these days multiple stakeholders such as artists, bereaved family, and foundations are more often participating as decision-makers, leading to the importance of their roles.Under these circumstances, we need to conduct research on methods of collaboration with stakeholders and on the scope of their rights in conservation treatment of the work. There is a need to approach these subjects from ethical/philosophical points of view other than the traditional conservation methods.

Thus, the aim of this study was in-depth research on a code of ethics for conservation of contemporary artwork and on the scope of rights of multiple stakeholders. Along the way, overseas case studies were reviewed and the kinds of stakeholders involved in conservation treatment were determined, along with how their opinions were reflected. In addition, citing conservation-treatment examples by the National Museum of Modern & Contemporary Art, Korea (MMCA), this study introduced the code of ethics applied in this museum. It also examined the efforts made to enhance the objectiveness and trustworthiness of conservation treatment while conducting close collaboration with stakeholders.

2. CODE OF ETHICS FOR THE CONSERVATION OF CONTEMPORARY ARTWORK

The materials used in contemporary art are more unstable and more subject to natural degradation than are traditional materials and each material conveys unique meaning. Therefore, contemporary works of art, have at times embarrassed conservators accustomed to traditional materials. As a result, academic societies have emerged, starting from D├╝sseldorf in the 1970s, to discuss this and related problems. Decades-long research on the scientific analysis of art materials and production methods, as well as conservation treatment methodologies, have brought forth the establishment of a data base for many works. Based on this, diverse conservation treatment methodologies were suggested (Wharton, 2015). However, the inherent meaning of the materials constituting the work and the artistŌĆÖs intention are neither easy to understand nor properly defined because of the peculiarity and uniqueness of each work. What must be noted here is that the immaterial, spiritual value of materials undergoing conservation treatment may play a key role in the work, and from time to time, the artistŌĆÖs message could be deemed more important than the material aspect of the work(Table 1). For this reason, replacement of the original materials constituting the work is permitted as one of the methods for conservation of contemporary art(Morera, 2017).

Meanwhile, the assertion of a pioneer of ŌĆ£traditionalŌĆØ conservation theory(Cesare Brandi, 1906-1988), that ŌĆ£only the material form of the work of art is restoredŌĆØ(Brandi, 2013) seems to be too restrictive to accommodate a theory of contemporary art conservation(Morera, 2017). His theory limited conservation of art to ŌĆ£maintaining the appearance of the work, that is, its original form,ŌĆØ overlooking the ŌĆ£artistŌĆÖs intentionŌĆØ and ŌĆ£immaterial standpoint of the work.ŌĆØ

Another pioneer in the conservation of contemporary art, German Heinz Alth├Čfer(1925-2018) asserted that conservation in contemporary art should be different from that of traditional art. He said the principle of ŌĆ£maintaining the workŌĆÖs appearance; the original form of the materialŌĆØ could be sacrificed, if required, to respect the workŌĆÖs spiritual value, in other words, the artistŌĆÖs intention(Alth├Čfer, 1991). In his book Contemporary Theory of Conservation, the Spanish conservator Salvador Mu├▒oz-Vi├▒as also said that contemporary art no longer belongs to an objective domain, but has crossed to a subjective one(Mu├▒oz-Vi├▒as, 2012).

According to the German conservator, Hiltrud Schinzel (1946-), the ŌĆ£workŌĆÖs appearance; componentsŌĆØ in contemporary art is directly connected to the artistŌĆÖs message and could be the outcome of expressing a contemporary Zeitgeist, the social/cultural context and thus the artistŌĆÖs message, physically. Therefore, she asserted that to realize complex elements inherent in the work it was necessary to actively engage with artists. This does not mean, though, that artists need to necessarily take part in the conservation treatment themselves. It implies that the artistŌĆÖs intention and thoughts should be included among the elements that must be considered significant in the process of decision-making for conservation(Hiltrud, 2004).

At the ŌĆ£From Marble to ChocolateŌĆØ conference held at the Tate Gallery, England in 1995, J. Heuman raised a question: "If the damaged part of the work were replaced with other material, does this damage the authenticity of the work? How should conservators respond if the artistŌĆÖs intention is in conflict with the preservation method?"(Heuman, 1995).

Foreign institutions such as the Netherlands Institute for Cultural Heritage(ICN) and the International Network for the Conservation of Contemporary Art(INCCA) are conducting research to actively involve artists in the conservation of artwork. They consider interviews with artists a central step that must be considered essential for engagement in the decision-making process.

Prof. Joyce Hill Stoner(1946-) from the University of Delaware conducted interviews with artists to record their standpoint and position in relation with possible changes resulting in degradation over time and consequential conservation treatment. Shelly Sturman at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC(USA) also emphasized the importance of collaboration with artists to enhance the objectiveness and trustworthiness of conservation treatment (Sturman, 1997).

As the importance of information about the work gathered from artists was discussed at an academic meeting of ŌĆ£Modern Art: Who cares?ŌĆØ held in the late 1990s, those at the ICN suggested and established how to interview artists and the directions of collaboration in cooperation with the Foundation for the Conservation of Modern Art(SBMK) and published a guidebook named Concept Scenario: Artist Interview(ICN and SBMK, 1999). At the INCCA, artists are considered important sources from which to collect information about the work. The institute also published the Guide to Good Practice: Artist Interview, which was to be actively used for conservation treatment(INCCA, 2002). Conversation between artists and conservators via interviews helps the latter to grasp an artistŌĆÖs intention, to record production techniques and materials used, and to collect the artistŌĆÖs standpoint regarding ageing or deterioration of their artwork. The planning of conservation treatment based on this plays a central role in the conservation treatment of contemporary works of art(Beerkens et al., 2012).

Discussion on a new code of conservation ethics able to secure the originality of contemporary artwork has been conducted robustly(mainly in Europe and America) and as a result, we have seen a diverse range of related symposiums and academic events take place. In 2012, the Getty Conservation Institute(GCI) hosted a discussion on the conservation of outdoor painted sculptures of the 20th Century. Among the many subjects discussed, ethical/philosophical issues and legal issues were treated significantly(Learner and Rivenc, 2013). Along the way, the International Institute for Conservation(IIC) held a congress, Saving the Now: Cross Boundaries to Conserve Contemporary Works, in 2016 in Los Angeles. There were discussions of practical and ethical/philosophical issues currently being confronted in regard to conservation of contemporary artwork from varied perspectives and approaches. As a result, many scholars insisted on the necessity of establishing a new code of ethics for the conservation of contemporary art, and animated discussions continue even now. Even so, no clear conclusion has yet been reached.

3. CONSERVATION OF CONTEMPORARY ARTWORK AND MORAL RIGHTS OF ARTISTS

To guarantee lasting interaction between the work and audiences requires preserving immaterial elements that render authenticity to the work, like the artistŌĆÖs intention, the message inherent in the work, and the social/cultural context. For this, collaboration with artists is more important than any other element.

Collaboration with artists not only works as an important element to enhance the appropriateness and trustworthiness of the conservation treatment of contemporary artwork but also is necessary to avoid violating the moral rights of the artist.

ŌĆ£Moral rightsŌĆØ, which are one of many rights included in a copyright, refer to the artistŌĆÖs rights related to his or her own work. Copyrighted artists have rights of integrity, which allow them to apply prohibition orders to address acts of distortion or unauthorized modification of their work. Conservation treatment methods could be irreversible in cases of repainting, repatination, or replacement of the original component materials for new media art, thereby causing issues with the originality of the work. In this case, it is highly likely to violate the rights of integrity(i.e., moral rights); consequently, collaboration with artists should be handled in a more careful and significant way.

Copyright for fine art had been discussed extensively around the globe, culminating in the ŌĆ£Berne ConventionŌĆØ which was established for the first time in 1886 to protect literary and artistic works. Our country(South Korea) joined this Convention in 1996. The initial Berne Convention did not provide moral rights, which were added later(1928). The USA joined the Berne Convention in 1989 and legislated the Visual Artists Rights Act(VARA) in 1990, which now protects moral rights for only certain visual works produced for the purpose of display.

Table 2 compares and summarizes each countryŌĆÖs legal clauses regarding rights of integrity. The terms ŌĆ£contentŌĆØ and ŌĆ£formŌĆØ that were stipulated in South KoreaŌĆÖs law Article 13, Section 1 could be interpreted as ŌĆ£internal formŌĆØ and ŌĆ£external formŌĆØ(Park, 2014). ŌĆ£Internal formŌĆØ could be understood as production intention of the artist and could be approached by respecting contexts inherent in the work. While external form can be classified as ŌĆ£appearance of the workŌĆØ and ŌĆ£materials of the work.ŌĆØ Therefore, if the internal form were maintained while the external form of the work was altered in the process of conservation treatment of contemporary artwork, this would not violate the rights of integrity. If the internal form were altered by distortion of the external form, it could be considered to violate the rights of integrity(Koo, 2010). This implies that understanding of the exact intention should be handled as a central issue for conservation treatment so as not to damage moral rights. However, there might be cases in which action taken would be contrary to the artistŌĆÖs original intention due to realistic limits such as expense or time required for the conservation treatment. ŌĆ£AlterationŌĆØ as done in a case like this would be considered ŌĆ£inevitable alterationŌĆØ with limited rights of integrity that should be applied in a limited way(Oh, 2016).

Furthermore, issues of copyright or ownership might arise in the process of decision-making in which multiple stakeholders(such as bereaved family or foundations) could participate during the conservation treatment of contemporary works of art. On the other hand, moral rights belong uniquely to a person, and are not transferable to others. Thus, they are rights owned only by living artists and when they die, the rights of integrity naturally cease to exist. Therefore, stakeholders like bereaved family or foundations are not able to have moral rights legally recognized.

4. EXAMPLES INVOLVING NEW CONSERVATION ETHICS FOR CONTEMPORARY ARTWORK

In this study, several cases involving new conservation ethics were examined, such as for the intervention of multiple stakeholders, particularly living artists, for the conservation of contemporary artwork.

ŌĆ£The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone LivingŌĆØ(1991) of worldwide artist Damien Hirst(1965-) was a case where the owner(not the artist) commissioned conservation treatments of a tiger shark preserved in formaldehyde because it had deteriorated.

At that time, extraordinary preservation methods were suggested like traditional methods of controlling the concentration of the formaldehyde and replacement of the shark. The artist replaced it with a new specimen of similar size. In an interview with the media, he mentioned that a shark was no more than a means to express death, so a shark of sufficient size to eat a human was more important than the particular specimen. This suggests that conveying the immaterial production intention of the artist to the audience may be more important than external, physical preservation of the work.

ŌĆ£Dirty CornerŌĆØ(2011) of Anish Kapoor(1954-) incited major issues like indecency, and was subjected to several attacks of vandalism while it was on display at the Palace of Versailles in France. In particular, vandalism consisting of expletives was covered with gold leaf by the artist himself instead of them being removed by a conservation treatment. For this, he said that the vandalism, part of the interaction with the audience, was an extension of the work. This is quite different from the existing positions taken regarding conservation ethics.

ŌĆ£VenusŌĆØ(1998) of the Korean artist(Mee Kyoung Shin, 1967-), was produced using soaps. It was designed so that it would naturally cease to exist over time, given the nature of soap. In 2009, she conducted a conservation treatment by applying varnish to the work surface herself in response to dissolution of the soap. This was contrary to her original intention when the work was first produced and suggests the need to re-establish the originality and authenticity of works undergoing conservation treatment in the future.

5. COLLABORATION WITH VARIOUS STAKEHOLDERS TO PRESERVE THE MMCAŌĆÖS COLLECTION

This part will be discussed the codes of ethics and communication between conservators, curators and artist for decision-making with case of conservation treatment in the National Museum of Mordern & Contemporary Art(MMCA).

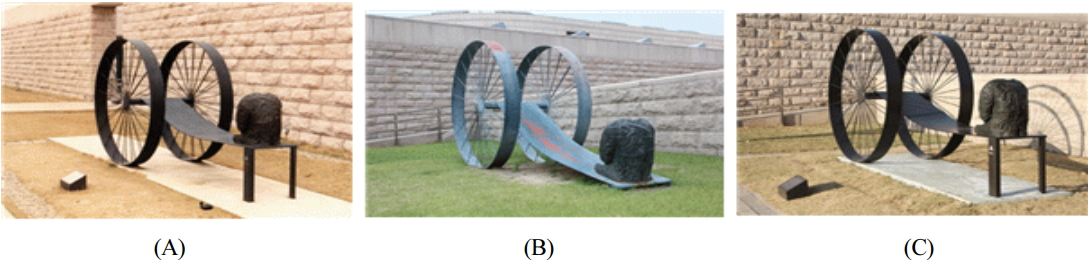

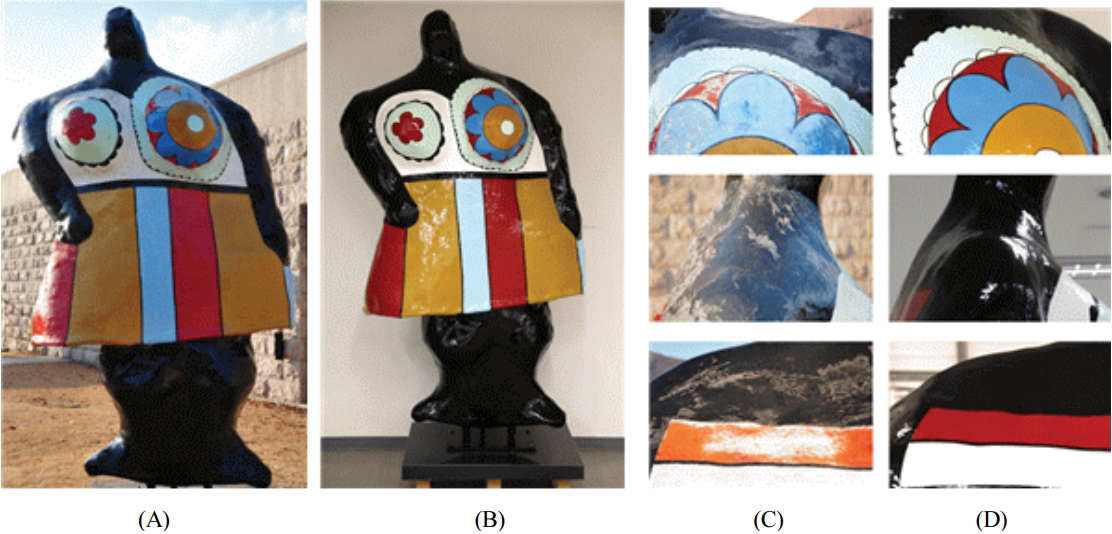

ŌĆ£Androgyn and the WheelsŌĆØ(1988/Color on steel, bronze) (Figure 1) of Magdalena Abakanowicz(1930-2017) and ŌĆ£Black NanaŌĆØ(1964/Color on polyester)(Figure 2) of Niki de Saint Phalle(1930-2002) were on display at MMCAŌĆÖs Gwacheon Outdoor Sculpture Garden. An extended period of open-air display caused discoloration and exfoliation of the two art pieces, and required urgent conservation treatment. Therefore, the MMCA prepared procedural measures for conservation treatment involving repainting via case studies at home and abroad. Scientific analysis and collaborations with internal, external experts(like artists and foundations) were engaged before performing objective and trustworthy treatment. In the case of ŌĆ£Venetian Rhapsody-The Power of BluffŌĆØ(2016-2017) of Cody Choi(1961- ), despite the current good condition of the work, it showed instability in the materials used in the work, including such as paints, neon signs, and photos on the canvas as well as indications of degradation. Therefore, to anticipate possible damage to the work later on, the MMCA discussed with the artist the need for conservation treatment and created an archiving process related to conservation.

5.1. ŌĆ£Androgyn and the WheelsŌĆØ of Magdalena Abakanowicz

The captioned work was produced based on the artistŌĆÖs design drawing as part of the ŌĆ£International Outdoor Sculpture Production on the SceneŌĆØ project in commemoration of the 1988 Seoul Summer Olympics.

As a result of internal meetings with personnel such as curators, registrars, and conservators for the conservation treatment of the work, they agreed to refer to painting information, color selection, and directions for the conservation treatment via discussion with the artist. Thus, the MMCA asked the artist to provide ŌĆ£documentary photography, records of the work at the time of production, types of paints, coloring, and direction of conservation treatment.ŌĆØ

The artist said: ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs already 28 years since its production and it was produced in Korea so I donŌĆÖt have the information of the work.ŌĆØ She also requested that MMCA selects the retouching colors in response to the photograph which taken in 1990 and contract of the work. And sends photograph to me after conservation work. Thus, based on colors and textures of still photos taken in 1990(nearest to the time of production), the MMCA produced four samples(30 ├Ś 30 cm) and selected colors after internal meetings before finally doing the repainting conservation treatment(Table 3).

5.2. ŌĆ£Black NanaŌĆØ of Niki de Saint Phalle

Consultation meetings with external conservation experts rised the need for a conservation treatment involving complete repainting was raised because there was much damage and severe discoloration. As a result of the first internal meeting among curators, registrars, and conservators of the MMCA, agreement was reached that, because the painting was so important in this case, the consent of the Niki de Saint Phalle Foundation was required for the repainting treatment. It was also agreed that the problem of shipping the work overseas for the work or having the conservation treatment done by a studio designated by the Foundation was hard to solve, so the MMCA needed to discuss this with the Foundation. The second internal meeting(with the director with the Conservation Treatment Science Team) resulted in the final conclusion that it should proceed after discussion with the Foundation. Thus, the MMCA sent a letter to the Foundation under the name of the director and got a reply from the Foundation, emphasizing that it was imperative that authorized conservators for restoration should perform conservation treatment for the authenticity of the conservation treatment of the work. It also required that the conservation treatment be performed only by professional conservation treatment studios(O. Haligon and two others) officially authorized by the Foundation for conservation treatment of her work. As a result of contacting the three studios, problems arose, including such as on-site oversight for the conservation treatment, expenses, and whether to proceed with conservation treatment abroad for fine art from the MMCA collection that was produced overseas. Therefore, a third internal meeting took place. In consideration of ŌĆ£management/oversight for conservation treatment,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£expenses of conservation treatment,ŌĆØ and ŌĆ£precedents of overseas conservation treatment.ŌĆØ The MMCA sent a letter to the Foundation raising the necessity for local conservation treatment. The MMCA received a final reply: ŌĆ£Trustees of the Foundation exceptionally decided qualified MMCA could conduct conservation treatment. It would be obliged if the MMCA submit report with details of used paint colors, used materials on completion of conservation treatment to the Foundation.ŌĆØ

In the fourth internal meeting, it was agreed that while the original form should be maintained, durable paints and coatings could be used as replacements at the time of selecting materials for conservation. The basic colors for repainting should be determined referring to the least discolored part. It was agreed to use the border side to the maximum in order to remove the old paint and to preserve the painting elements of the colored portions at the time of repainting. Moreover, the repainting conservation treatment was carried out according to the decision that the paint brush strokes of the artist-partly viewable-should be reproduced to the fullest, based on existing photographic data and the currently existing parts(Table 4).

5.3. ŌĆ£Venetian Rhapsody-The Power of BluffŌĆØ by Cody Choi

The captioned work of Cody Choi, who participated in the 2017 Venice Biennale as one of the artists at the Korean Pavilion, was made from neon electronic signage on painted steel with gorgeous animal patterns of dragons, tigers, and peacocks. In addition, his own advertisement for an antacid(Pepto Bismol®) was shown in the photograph printed on canvas(Figure 3).

For his work, which was recently produced(2017), there was no problem of preservation at all for the display. However, in consideration of possible exfoliation, discoloration of the printed layers, replacement of the neon lamps, and of the photographic prints on canvas in the future, the MMCA prepared for a discussion with the artist about conservation treatment starting at the collecting stage, and then archiving to provide prevented conservation treatment in advance.

Above all, the MMCA recorded the images and their conditions by survey at the time of collecting the work. In order to select the current colors of the work as the basic colors, the MMCA cleaned pollutants from the work surface using distilled water. Then, it compared each of the basic colors of the work and comparative color groups using color charts(Dupont, Pantone) as per Table 5, before selecting a reprinting color table in the first place. In addition, the MMCA measured chromaticity and gloss of the work by comparing them with colors on color charts, which were confirmed by naked eyes, a spectrum colorimeter(CM-700d, Minolta, JPN), and a glossmeter(Micro-TRI-gloss, BYK Gardner, DEU).

The MMCA, assuming the circumstances requiring conservation treatment in the future based on the materials archived initially, conducted interviews with the artist. The content of the interviews was archived along with video shot following his consent to the conservation treatment. The main content of the interview was as follows. ŌĆ£The artist agrees to the use of reprinting conservation treatment in the future based on archived data(colors, glosses) done through scientific examination of the MMCA. Besides, should the production of neon lamps at home and abroad be stopped, they could be replaced with similar LEDs or stable illuminations, and color temperatures of the current illuminations would be archived as records. Lastly, because the photograph printed on canvas is exposed outdoors, reproduction of the image using similar canvas would be possible in fear of degradation, while image files could be demanded personally by the artist because of copyright problem.ŌĆØ In this way, the MMCA tried to ensure the originality and authenticity of the work to the maximum extent possible via collaboration with the artist as to the conservation of his artwork.

6. CONCLUSIONS

It is difficult to predict the kinds of damage to contemporary art because of the diversity of materials and experimental techniques used. This makes it hard to conserve. As for the makers of contemporary art, the materials and expression skills used for fine arts are no longer the means to show their capability. They have transformed media to convey their own messages, thus it is necessary to approach contemporary art with ethical/philosophical points of view different from the traditional code of ethics for conservation. The traditional view emphasizes treatments that maintain the original form, are reversible, and that adhere to minimum intervention for conservation.

In contemporary art, in particular, conservators often need to perform conservation treatments focused on maintaining the artistŌĆÖs ŌĆ£intended appearance.ŌĆØ Thus, determining the artistŌĆÖs intention and information about the artwork provided by the artists themselves from the start of planning conservation treatment is becoming more important. Consequently, collaboration with artists is currently a matter of lively discussion in the field of conservation as one of the most important issues. Of course, all the opinions of the artist are not able to be accommodated in an absolute way. However, should reprinting of outdoor painted sculptures or repatination of bronze sculptures be required, or should irreversible treatment be required like the replacement of monitors for new media work, close discussion with the artists must play a central role in the decision-making process for conservation. However, it is not easy for artists to remember all of the materials and techniques they might have used, and mistakes might occur. Therefore, conservators should render effort to enhance the trustworthiness of the conservation treatment using scientific analysis and research.

The aim of this study was to identify procedural measures like ŌĆ£moral rightsŌĆØ extended to living artists, and to survey the methods used to collaborate with other stakeholders (bereaved family members, foundations, and owners) who might participate in conservation treatment. Unlike with the traditional code of ethics for conservation, in this study, overseas examples were used to examine new approaches to conservation ethics. These include the artistŌĆÖs intention(i.e., the spiritual value) as well as the understanding and respect of immateriality inherent in the work along with the processes to resolve obstacles along the way. Last, the study used examples of conservation treatment by the MMCA, to introduce its code of ethics for conservation and for collaboration with various stakeholders to enhance the objectiveness and trustworthiness of conservation treatment.

It is expected that the findings of this study could be used as fundamental data to establish a code of ethics for the conservation of contemporary art and its directions.